Make blue dye from red beetroot – chemists devise a new pigment option

Blue is strongly associated with nature, reflected in the sky and on bodies of water. But blue is not commonly found in living organisms.

Erick Leite Bastos, Universidade de São Paulo

What’s your favourite colour? If you answered blue, you’re in good company. Blue outranks all other colour preferences worldwide by a large margin.

No matter how much people enjoy looking at it, blue is a difficult colour to harness from nature. As a chemist who studies the modification of natural products to solve technological problems, I realised there was a need for a safe, nontoxic, cost-effective blue dye. So my Ph.D. student, Barbara Freitas-Dörr, and I devised a method to convert the pigments of red beetroot into a blue compound that can be used in a wide range of applications. We call it BeetBlue.

Natural sources of blue

The feathers of many birds are blue, not because they produce a pigment, but because the microscopic structure of their feathers is able to filter light. This physical phenomenon is very interesting but difficult to adopt for common applications.

Plants seldom produce blue hues. When they do, their pigments rarely remain stable after extraction. The same is true for blue mushrooms like the indigo milky cap and other species that develop a blue stain when disturbed.

Turning red into blue

You might wonder how something red can be turned into something blue. One approach is to change the way its molecules absorb and reflect light.

The white light coming from your lamp contains a rainbow of colours, even though you cannot see them – without the use of a prism, that is. The surface of your red chair looks red because, at the molecular level, it is absorbing all the colours except red, which is reflected and eventually reaches your eyes.

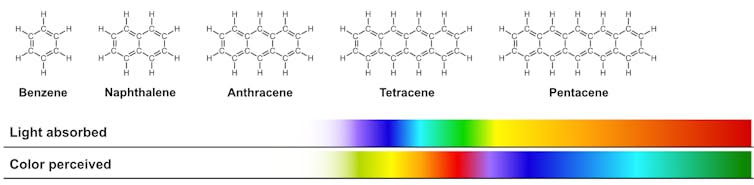

The colour of your chair would change from red to blue if you modified the molecular structure of its dye, making it reflect blue light instead of red. The secret is in the number of carbon atoms in the dye and how they are connected to each other.

Beetroot produces chemical compounds called betalains, which are natural pigments and antioxidants. The chemical structure of betalains can be modified to produce almost any hue. We realised that if we increased the number of alternating single-double bonds in betalain molecules, we could change their colour from orange or magenta to blue.

Making blue dye with adequate intensity and light-fastness is difficult because it must absorb yellow and orange light efficiently. Solving this problem required lots of molecular tweaking.

My lab has been working with betalains for over 10 years to understand their function in nature and their unique chemical features, so it took only one experiment to produce BeetBlue. (It took more than two years to optimise the process, though.)

We broke apart the betalain molecules using alkaline water with a pH of 11. Then we mixed the resulting compound, called betalamic acid, with a commercial chemical compound called 2,4-dimethylpyrrole in an open vessel at room temperature. BeetBlue is formed almost instantly.

Because we changed the characteristic carbon-nitrogen chemical bond of betalains into a carbon-carbon bond, BeetBlue is a new class of pseudo-natural dyes we call quasibetalains.

Colour your life blue

The chemical synthesis of BeetBlue is fast and very simple. In fact, it is so simple that anyone can do it if all the chemicals are available.

BeetBlue dissolves easily in water and other solvents, maintains its colour in acidic and neutral solutions, and may provide an alternative to expensive blue colourants that often contain toxic metals, which limit the scope of their applications.

Live zebrafish embryos as well as cultured human cells were not affected by BeetBlue. Although more experiments are necessary to make sure it is safe for human consumption, maybe you can dye your hair, customise your clothes or colour your food in the future using a dye made from beetroot.

This work shows the importance of basic science for the development of technological applications. We did not patent BeetBlue. We want people to use it freely and understand, by interacting with nature in a different and sustainable way, the future can be bright.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

Erick Leite Bastos, Associate Professor of Chemistry, Universidade de São Paulo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.